Pedro Noguera’s

City Schools and the American Dream (2003) is an empowering text that refuses to contribute to society’s negativity regarding America’s urban schools. Noguera points out the interdependent relationship between schools and society, and he posits that America’s children are not the sole responsibility of her education system. Although Noguera seems to imply a competition between society and its schools for the attention and enthusiasm of American children, he assures readers that the solution is well within reach: America’s schools and societies must get on the same proverbial page, a page of communication, motivation, and commitment. The question remains, however: How, in a world of economic distinction and cultural diversity, can a single social identity be identified and worked toward? Noguera emphasizes the need for partnerships between communities and schools, a linkage of educational and environmental issues. Just as schools must address a student’s basic needs while affirming his goals and values, they must also have their own values that encourage bonds among administrators and educators to promote positive change. By systematically examining the current “crisis” of America’s urban schools through social, cultural, environmental, and academic contexts, Noguera ends with a hopeful charge that those who understand the extent of education’s possibilities will work deliberately and without delay to inform others and encourage them to collaborate and commit to improving America’s schools. Her future depends on it.

Noguera has done extensive research and has an impressive background in education. His self-proclaimed “critical support and pragmatic optimism” regarding urban public schools is encouraging, and although his claims are well-founded in his own and others’ research, they do not branch beyond the San Francisco Bay area. It would be interesting indeed to know how the data of his small section of California matches up with other major metropolitan areas such as Chicago, New York City, or even Atlanta. Additionally, it was hard to tell if some information was gathered from students, parents, or objective data collection. When Noguera mentioned, for example, that Black and Latino students are more likely to garner suspicion when walking through the hallways than White students, did this come from the “suspicious” students or suspecting staff members? Student perceptions of adults’ perceptions are not always accurate; therefore, it would be helpful at times to have data to back up certain subjective statements.

One of the biggest assumptions Noguera seems to make is that all urban public schools are similar to those within the San Francisco Bay area. As his main solution to the issues in urban schools is for there to be more significant collaboration among schools and their communities, he further makes the assumption that these two entities—school and society—are so strongly interrelated that when one fails the other is likely to also. Even if the school-society relationship is undoubtedly a significant one in San Francisco, can it be assumed that this is the case across the U.S.?

Additionally, if a particular school is thriving, is it truly because of an extensive, positive collaboration among the civic-minded, or is it because that particular district or school community has many members with significant social capital who know how to make the system work for them? If education is to be the “equalizer” of opportunity (p. 22), Noguera seems to assume that those with opportunities will take advantage of them. How can that be assured? What can be done to increase intrinsic motivation? How can one strengthen the social capital of those who sense no immediate benefit and aren’t willing to divert from their norms?

Further, Noguera makes the assumption that the label community is a positive one. In Robert Putnam’s

Bowling Alone, he asserts that the effects of social capital can sometimes lead to tragedy, most notably the Oklahoma City bombing and the emergence of the KKK (2000). How can it be assured that any created community will benefit not only its members but also those within its grasp?

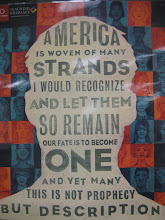

For the sake of argument, say members of a particular community are willing to collaborate in a “positive” and beneficial way, and say PS #84 has excellent leadership able to motivate its faculty. But where does the single vision come from? Who decides which battles are worth fighting and which should be ignored? Noguera seems to assume that the “crisis” with urban public schools is one that can be solved with collaboration; however, the nuance of educational policy will keep the solution from being that easy. Think semantics: Who would argue against legislation titled No Child Left Behind? Yet there are many aspects of this act that are not beneficial for American students, and there are countless educators who abhor some of its implications on schools. The question remains: Even if members of a school community are willing to collaborate, how will they agree on what message with which to collaborate? Noguera acknowledges the difficulty of creating a collective identity, and his answer to the above question would likely deal with empowerment; he would likely assert that both students and parents need to feel safe, respected, and empowered; they need to have information and opportunity and encouragement. It’s the individuals who understand this, who are not threatened by empowering the masses, who must take the charge to lead education into a future marked by confident, knowledgeable students of the world.

Noguera is a clear proponent of Horace Mann’s philosophies, especially, as mentioned earlier, Mann’s belief that American schools as an institution is “an arena where inherited privileges [should] not determine one’s opportunities (p. 22). Additionally, Noguera mentions Brazilian Paulo Freire, an educator who sees education as a way to equip students to discover their ever-changing role in a transitory world. Noguera seems most intrigued by Freire’s notion of the “limit situation,” and this major tenet can be sensed throughout Noguera’s text. Freire’s idea is that when it comes to adults who have problems reading and writing it is not because of mechanics but rather because of feelings of powerlessness. While Noguera doesn’t focus solely on literacy, the center of his argument deals with making certain that students and parents alike feel connected and important to a child’s education. There is little concentration on data and numbers compared to Noguera’s emphasis on relationships and connections.

It is likely Noguera is also familiar with John Dewey, who acknowledged the variety of influences that shape one’s character and saw a great opportunity within schools to make positive change, provided that they are “organized as a community” (qtd. in Rosario, 2000, p. 33). (For all intents and purposes, it can be assumed that the term “community” is used in the most positive sense.) However, an important distinction exists: school communities need to—as quoted in Jose Rosario’s chapter in Curriculum and Consequence (2000)—“see that they are a part of the larger school and not separate entities unto themselves….[W]e also need [students] to understand that this community is only part of the whole society” (p. 41). Although Noguera does not mention the philosophies of educational gurus such as John Dewey by name, concepts of community have been studied for years, and Noguera has surely done his homework.

This text has been remarkable in stimulating considerations regarding school-community connections. Although there are tremendous possibilities for change in American public schools, as Noguera (2003) notes, “Public education is one of the few enterprises where the quality of service provided has no bearing whatsoever on the ability of the system to function” (p. 15), and that is a frightening thought. The most lasting impression Noguera’s text gives, however, is a sense of empowerment for educational stakeholders. He makes it seem possible that those who “get it” can successfully encourage others to stake their claim in the future of education, and that, little by little, America’s public schools can make a change for the better. Although the school-society relationship is reciprocal, change truly does need to start in the schools through motivated educators. One of the toughest challenges, though, is finding ways to recruit the quality people into the profession, and even beyond that is making certain these quality people understand the power they have and the most effective ways in which to use it. What is the potential power that these professionals have? To empower others. By helping to develop mindsets within students that they are worthy of opportunity and choice, and by encouraging them to take advantage of the organizations and classes available to them, educators can begin to shift the social paradigm that labels and limits “urban” kids.

The clearest way to encourage and perhaps even mold future educators lies in the teacher preparation provided by colleges and universities. Maslow, Dewey, and Piaget are all important names to know with philosophies worth studying; however, just as critical is developing an educator’s methodologies and philosophies that ultimately support a civic-mindedness. This is not an impossible feat; future teachers need to be aware of just how many resources are available for developing lessons that both meet state standards and create readers of the world, and they need to understand the dire importance of instilling this skill in their students. Read Chaucer and discuss sexism; point out the oppression in Hugo’s Hunchback and write problem-solution essays on how the oppressed can break the cycle; have students create public service announcements and post them around the school or read them on the daily announcements. Little by little, as students begin to understand the authority they have in their own lives and the responsibilities they have in the lives of others, American society will shift… and so will the “crisis” marking urban public schools.

Noguera, P. (2003). City schools and the American dream. (J.A. Banks, Ed.). New York: Teachers College.

Putnam, R.D. (2000). Bowling alone. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rosario, J.R. (2000). “Communitarianism and the Moral Order of Schools.” In B. Franklin (Ed.), Curriculum & Consequence (pp. 30-51). New York: Teachers College.