Reflecting on Chapters 1-3 of Developing More Curious Minds

“The Cost of Your Ego”

“But what makes it urban?” I am inevitably asked this question when I talk about my enthusiasm for and dedication to urban education. It’s not a difficult question to figure out; just picture an inner-city public school system. No, seriously: Bullet a mental list of the qualities you think make, say, IPS IPS. (I’ll give you a minute….)

Now consider a township school. What traits would make it onto that bulleted list?

Your perceptions and stereotypes exist for a reason, and they’re probably close to accurate. The inequities between an urban school and a township school are both distinct and destructive. Because of the socioeconomic disparities that exist among neighborhoods (“Children living in urban areas are much more likely to be living in poverty than children in other types of communities,” the University of Michigan reports), and because poverty has been strongly correlated with race and ethnicity, inner-city schools face many issues that others can often rather easily ignore. And think about it: If you aren’t worried where your next meal is coming from or whether to use the last of your paycheck to buy groceries or pay rent, how much more energy can you spend on ensuring you—or your children or your students—are getting what they need and deserve in an education?

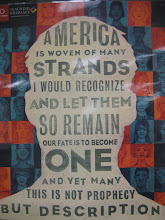

So that begs the question: What do kids deserve in school? What kind of education should America provide for all students? Personally, I maintain that all students deserve an education that empowers them, that liberates them, that shows them they have choices in life; in “eduspeak,” that means I advocate critical pedagogy. This methodology encourages students to question their realities; challenge the status quo; resist passive acceptance. Sounds like a good idea, right? Helping students develop into actual thinkers? So why don’t more teachers make this effort?

Educator John Barell (2003) offers a few reasons:

• Asking hard questions can be “viewed as offensive” (p. 6).

• “Being questioned about anything often leaves some of us feeling uncomfortable” (p. 7).

• “We are threatened by questions, fearing loss of control” (p. 7).

Makes sense, right? Haven’t teachers historically been the “sage on a stage,” lecturing their classes and leading them through exercises that prove mastery of academic standards? Unfortunately, it almost seems as though teachers forget that, as Barell quotes from Wolfe & Brandt (1998), “Learning is a process of active construction by the learner” (p. 12). So how do we reconcile mapping our curriculum/aligning it to standards with the empowering—and organic—process of constructing knowledge? If we want youth to develop into thinkers, imaginative creators, active citizens in our nation’s democracy, then we have got to start encouraging them to ask questions to which we don’t already have the answers.

Barell mentions a story in Developing More Curious Minds about a young boy whose mother would not ask, “Did you learn anything today?” but rather, “Did you ask a good question today?” This is precisely the mentality all educational stakeholders must adopt if we want to give our youth the empowering education that they deserve. Do our students know how to ask “good” questions? Do they understand the difference between, as Bowen (2001) would describe, “fat” and “skinny” questions? When Barell refers to a teacher at Monroe Middle School who asks her students at the beginning of the year “What questions do you have about the world?” (p. 31), part of me wonders the extent to which our students do wonder about the world. Too many times I have attempted to encourage inquiry only to be met with huffs and whining. “Just tell us what we need to know!” my sophomores have pled. Sure, giving them a list of prepositions to memorize may be easy for them to learn and even easier for me to grade, but is this doing anything to create a curiosity in them that will produce lifelong learning?

The point of all of this? Inspire inquiry, teachers! Ask, students! Never be afraid to say, I don’t know, but let’s figure it out! Is it scary to not know the end before the means? Is it uncomfortable to have more questions than answers? Sure. But this is precisely the culture that America’s system of education must transition towards to shorten the distance between the inner-city and the suburb; truly, a culture of inquiry doesn’t cost a thing but your ego.

References

Barell, J. (2003). Developing more curious minds. Alexandria: ASCD.

Bowen, C. (2001). A process approach: The I-Search with grade 5: They learn! Teacher Librarian, 29(2), 14-18.

University of Michigan. (2009). Urban education. Retrieved from //sitemaker.umich.edu/rosman.356/urban_education_