James Noll puts it best in his overview of Issue 9 in Taking Sides: Clashing Views on Educational Issues when he observes that there is a “direct impact of test mania on the nature of the learning process” (2007). In short, Noll’s statement sums up why my connection to the issue of high-stakes testing is so important: ultimately, it is my job to analyze my students’ learning processes and figure out the most effective interface between my methods and their abilities; I must be aware of and understand the various contexts affecting each student’s learning. Further, I am a constructivist. There are innumerable ways to measure students’ skills and capabilities, differentiated ways that allow for individual accommodations and provide a respect for diversity. As teachers, we are continually challenged to develop professionally, to create innovative lessons and find new ways of reaching our students. I refuse to accept the disparity between what teachers’ assessments in the classroom are expected to look like and what the state’s assessments have become.

In terms of a personal context for this assertion, I have just a couple notations. First, I was raised in a Chicagoland suburb and attended schools where the majority of the student population was just like me: white and middle class. I was always a good student, taking honors and AP classes and getting involved in choir and drama. I say these things to be clear that my motivation in developing such an emotional, negative opinion about high-stakes testing is not due to a particularly bad experience that I had in my youth. In contrast, I scored well on Illinois’ IGAPs and never felt lost or confused because of misunderstanding the language of the test. My distaste for tests such as Indiana’s ISTEP+ actually only developed as I began instructing the ISTEP+ remediation academy that met for two hours after school on four weeks of Tuesdays and Thursdays. In this time I met countless ENL students who could hardly communicate with me, let alone read or understand the directions on an exam. Additionally, I met many students who were incredibly capable of passing but just didn’t care, and I also worked with students from honors English classes who just couldn’t seem to pass the ISTEP. The most eye-opening moments, however, came as I began preparing the review materials; some of the questions were worded incredibly awkwardly, and I didn’t always understand what some prompts were trying to get at. With my combination of having degrees in both English and Secondary Education and graduating from Butler University Cum Laude, imagine my feelings of inadequacy at getting stumped by the ISTEP! I cannot even fathom the confusion and aggravation of students whose fortes do not include reading comprehension or essay writing. Further, the rubrics for the essays allowed little to no room for creativity or outside-the-box thinkers. If students didn’t write a standard five-paragraph essay addressing the bullet-pointed prompt precisely, they were unlikely to score well. In a system where teachers are to encourage discovery and independent thinking, is it not contradictory to assess them via prescripted formats? I do understand that to be successful in a global market we all need to be able to understand and adhere to protocol, but I still feel strongly that more liberties need to be taken to look at a student’s test—his essay especially—holistically.

I truly enjoyed the Hurwitz and Hurwitz’s “Tests That Count” and Ken Jones’ “A Balanced School Accountability Model: An Alternative to High-Stakes Testing” because each made points that required me to sit and think. I found myself writing several combative questions in response to Hurwitz and Hurwitz’s suggestions, and, in contrast, I marked many lines in Jones’s that resonated with me as I nodded along with his observations and calls for action. Let me begin with a couple of my challenges. Hurwitz and Hurwitz note that in order to make high-stakes tests “work,” “learning not testing [should be] the goal” (2000). My thought about this is twofold: First, if there is a test given by the state, does preparing for it not inherently become the goal? Don’t teachers develop objectives before lessons and plan assessments based on objectives? Second, if learning is the goal, can it not be assessed in a variety of ways? Shouldn’t it be assessed in a variety of ways? I just don’t understand how Hurwitz and Hurwitz can support testing by asserting that learning needs to be a school’s true goal or that testing can accurately measure such learning.

In another section Hurwitz and Hurwitz claim that “there has been a heavy investment in addressing the academic performance of the weakest students” (2000). My question here is about the methods; how is the money being used to improve weak students’ performance? In workbooks? In paying teachers to instruct tedious after school skill-drills? Without knowing how this funding is being used, it is unfair to judge Hurwitz and Hurwitz’s point; however, it is likely the means of addressing weak students’ performance are not innovative or engaging, and I just don’t see how such means would encourage learning or adequately prepare students for success in the global market.

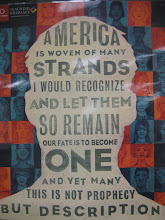

In contrast to my continual skepticism of Hurwitz and Hurwitz was my appreciation of Jones’ text. One of the most poignant points Jones makes is that “A standardized approach toward school accountability cannot work in a nation as diverse as the U.S.” (2004). Teachers need to be trusted to adjust their methods to the contexts of their classrooms. We know better than anyone what will and will not work for getting our students to reach the objectives and standards set by the state. Further, not only will flexibility in assessing schools help reestablish teachers’ feelings of professionalism (which Jones argues is waning), but it also has the power to put the emphasis back on learning, not testing, as Hurwitz and Hurwitz noted as necessary.

Jones also asks the question, “How can students be expected to meet high standards if they are not given a fair opportunity to learn?” (2004). Although I agree strongly that schools need much more equality in terms of funding and resources, I think Jones’ question is a gross oversimplification; there is so much more to a “fair opportunity to learn” than what an institution can offer. Consider the impacts of socioeconomics or race; what can a school do to change a student’s environment once the bell rings at the end of the day? Is it fair that one student goes straight to work after school and has little to no time to complete homework or study, yet another goes home and has the evening free to do homework on the computer, study for an upcoming test, get help from an older sibling? Each student’s background and home life contribute significantly to his success in the classroom, and I think it’s important to understand that educational institutions cannot erase these influences but should be especially cognizant of them in their effort to be “fair.”

Before reading these articles I knew that I was not a fan of high-stakes testing, although all I could really say about it was that the tests were often called culturally biased and that ENL students were counted in the school’s statistics, which I found remarkably unfair and inaccurate since many of these students are extremely limited in their English proficiency; their failure of the ISTEP+ is no indicator of their intellect. However, I can now better articulate the reasons why high-stakes testing doesn’t make sense; I can discuss the differing considerations affecting a student’s schooling and can point out which of these are neglected by using standardized tests to hold schools and teachers accountable for student achievement. Therefore, whereas I have not changed my opinion, I have shaped my perspective. I can now engage in discussions about testing with more confidence and evidence. Further, I will continue to focus on learning in my classroom, and I will continue to give a variety of assignments and assessments. Because there are such high stakes when it comes to ISTEP+ scores, though, I must still help my students learn how to become effective test takers and how to answer essay questions to earn the most points. I will still go over scoring rubrics with them. But I will not pour all my energy into teaching them to take a test, for that will do little to truly prepare them for emerging into successful people with integrity and character. In all, it is incredibly reassuring to me that there is literature out there testifying to the inanity of objective assessments. There is hope that this, too, shall pass.

Noll, J.W. (Ed.). (2007). Taking sides: Clashing views on educational issues (14th ed.). Dubuque: McGraw-Hill.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment